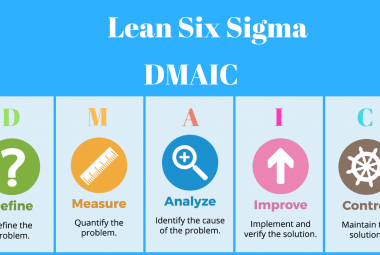

Projects are an important part of every lean program. First, you have the small problems that can be solved within the team and then you have the larger problems that can be solved with the use of A3 thinking. There are however bigger structural problems that can not simply be solved within a few weeks. These are the projects. Projects can take up to six months to complete and traditionally follow 5 Phases within (Lean) Six Sigma: define, measure, analyze, improve and control (DMAIC). I prefer to use the D2MAIC structure described by Abramowich (2005), which starts with a Discovery phase before the Define phase. This article describes the first two phases of the D2MAIC structure, the discovery and de define phase, at its most basic level, which is commonly refered to as Yellow Belt.

The DISCOVERY PHASE takes place before the project starts and is part of the strategic plan of an organization. The X-matric, Profit and Loss waterfall and Pareto analyses can help determine where the next project should be focused on.

The discovery phase can therefore take place as part of Hoshin Kanri, where next year’s targets are defined using the X-matrix. Within this x-matrix, you move from strategies, to results, to processes and finally tactics (Jackson, 2006). In this case, the future project is the tactic, which focusses on machine 4 (process) to achieve a downtime reduction directly reducing conversion costs (results). Figure 1 shows an example of an X matrix template.

Figure 1: example X-matrix

Now, the strategic part of the project is set. We know that we have a realistic opportunity for improvement which directly leads to measureable results. The next step is to start working on the project charter. In the discovery phase you only define the first two parts of the charter: the problem statement, with the improvement goal, the time line and the scope of the project, and the team structure with roles and responsibilities.

Usually, this is done in a kick-off meeting, where the team comes together for the first time and discusses all the above.

Questions that need to be answered before the Hoshin is complete, and before the project starts are: what is the gap that we like to close? How much are we going to save? Who is going to be in the team and what are the risks?

The profit & loss statement is a leading tool in defining the goals of a project that directly lead to bottom line results. Since preferably, every project should directly influence bottom line results, we should define our projects based on where most of the losses occur. The Waterfall chart can help visualize these losses. Figure 2 is an example of a waterfall breakdown for a machine park in an example factory. By splitting OEE numbers in different categories, the chart shows that most losses occur in the machine availability category. Of course you can split losses in any other possible way that helps you in your organization; the OEE is just one possibility.

After this waterfall, it is possible to break one of the aspects down a level deeper. As a next step we could create a waterfall chart for availability only, to see what factors influence this indicator the most.

When creating these charts, keep them money focused. The deeper you go into the waterfall, the smaller the individual parts will be. In the end we would like to select an indicator to improve based on a saving that is worthwhile the resources necessary to complete the project.

Figure 2: example waterfall chart

The Pareto Analysis can then help to define what improvement gaps there are. In Figure 1 we found, that half of the OEE losses are due to availability of the machines. It makes sense to see what the difference is between the different machines in the factory. Figure 3 shows an example Pareto of downtimes for 7 machines.

Assuming these are 7 parallel machines, this graph shows that machine 4 has a downtime of 20%, while machine 3 only has a downtime of 5%. Because machine 3 proves that it is possible to have downtimes of only 5%, it could be worthwhile to define a project that reduces the downtime of machine 4 from 20% to 5%, with the possible benefit that we can copy the results to the other machines as well. Before we start the project, we calculate how much we would save by reducing the downtime of machine 4.

Figure 3: example Pareto Chart

Finally, the discovery phase should include a risk analysis. What are the possible risks for this project? Different risks are mapped on three scales: the chance that it happens, the impact that the risk has on the organization and how well we can detect the risk when it occurs (Abramovich, 2005). This is also referred to as the Failure Modes and Effect Analysis (FMEA)

The next project phase is THE DEFINE PHASE. This phase has at least three goals: understanding customer requirements, gaining a general understanding about the process and finalizing the business charter. Each of these goals can be achieved using a variety of tools. My favourite tools to use in the define phase are the SIPOC and the critical to quality analysis based on the Voice of the Customer (VOC).

The SIPOC (an acronym for supplier, input, process, output, and customer) is a model that is used to visualize the complexity of a process. The SIPOC helps to identify the different stakeholders of a process (suppliers and customers) which helps the project team to define their communication plan and the definition of the voice of the customer. More information about the SIPOC can be found in the article: the Lean toolbox - SIPOC. An example of the SIPOC is shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: SIPOC example

In the critical to quality (CTQ) analysis, the project team define the customer requirements and how the product and or process deliver those requirements. The voice of the customer (which can also be the voice of the business) can be both internal and external. In its simplest form, the CTQ analysis can be a table as shown in figure 5.

The project team can list different stakeholders, their most important topics or indicators, and the critical requirements that need to be met by the process, which helps the project team in fine-tuning the project goals.

Figure 5: example critical to quality analysis

At the end of the define phase, the project charter that was started in the discovery phase is continued. The project team has now gathered more information about the project and can update the problem statement, the goals and scope of the project with the project sponsor(s).

After doing the SIPOC and CTQ analysis, a more precise business case can be built to show the value for the business when this project is done, not only money wise, but also how we can improve customer satisfaction.

Continue to:

Yellow Belt DMAIC (2/3): Measure and Analyse

REFERENCE:

Abramowich, E. (2005). Six Sigma for Growth - Driving Profitable Top-Line Results. Singapore : John Wiley & Sons. (order this book)

Jackson, T.L., 2006, Hoshin Kanri for the Lean Enterprise – Developing Competitive Capabilities and Managing Profits, Boca Raton (FL, USA): CRC Press (order this book)